By Andreas Schleicher

Director, OECD Directorate for Education and Skills

The backdrop to 21st century education is our endangered environment. Growing populations, resource depletion and climate change compel all of us to think about sustainability and the needs of future generations. At the same time, the interaction between technology and globalisation has created new challenges and new opportunities. Digitalisation is connecting people, cities, countries and continents in ways that vastly increase our individual and collective potential. But the same forces have also made the world volatile, complex and uncertain.

In this environment, the Sustainable Development Goals, set by the global community for 2030, describe a course of action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all. These goals are a shared vision of humanity that provides the missing piece of the globalisation puzzle, the glue that can counter the centrifugal forces in the age of accelerations. The extent to which those goals will be realised will depend in no small part on what happens in today’s classrooms. Education will be key to reconciling the needs and interests of individuals, communities and nations within an equitable framework based on open borders and a sustainable future, and it will be key to ensuring that the underlying principles of Sustainable Development Goals become a real social contract with citizens.

Schools need to help students learn to be autonomous in their thinking and develop an identity that is aware of the pluralism of modern living. At work, at home and in the community, people will need a broad comprehension of how others live, in different cultures and traditions, and how others think, whether as scientists or as artists.

These considerations have led PISA to include ‘global competence’ in its tri-annual assessments. To do well on this assessment, students need to demonstrate that they can combine knowledge about the world with critical reasoning. PISA also examines to what extent students understand and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others. And PISA surveys students on their disposition to adapt their behaviour and communication to interact with individuals from different traditions and cultures.

At work, at home and in the community, people will need a broad comprehension of how others live, in different cultures and traditions, and how others think, whether as scientists or as artists

It is perhaps no surprise that countries that do well on PISA’s assessment of reading literacy, i.e. where students are good at accessing, managing, reflecting on and evaluating information, also tend to do well on the cognitive test that was part of PISA’s assessment of global competence. So the high-performers Singapore and Canada also come out on top in global competence. What is more interesting is that PISA high performer Canada does even better on global competence than what the high performance of its students in reading, math and science predicts. Equally interesting, Colombia’s students often struggle with the PISA reading, math and science tasks, but do far better on global competence than predicted by their reading, math and science skills. This country once torn by civil war made significant efforts to strengthen civic skills and social cohesion over the last decade, and that seems mirrored in the learning outcomes at school. To a somewhat lesser extent, students in Scotland (United Kingdom), Spain, Israel, Singapore, Panama, Greece, Croatia, Costa Rica and Morocco also do better in global competence than predicted. In turn, students in Korea and the Russian Federation do less well in global competence than what their performance in reading, math and science predicts.

But the most interesting finding from this new PISA assessment is that many school activities, including the organisation of learning at school, contact with people from other cultures and learning other languages, are positively associated with global competence.

Let’s look at some of those findings in turn.

What schools can do to support learning about global issues and intercultural understanding

According to school principals, the most common learning activities to support global competence at school were learning about the beliefs, norms, values, customs and arts of diverse cultural groups and learning about different cultural perspectives on historical and social events. Less common were celebrations of festivities of other cultures and student exchanges with schools from other countries.

In many countries, the number of such learning activities in which students engage is positively associated with students’ attitudes and dispositions. That is, students engaged in a larger number of learning activities around global competence tended to report more positive attitudes and dispositions to other people and cultures than students engaged in fewer activities.

In many countries, the number of such learning activities in which students engage is positively associated with students’ attitudes and dispositions

The findings also show large differences in the extent to which global issues (public health, climate change, poverty, migration and conflicts) and intercultural understanding (communication with people from different cultures, openness to intercultural experiences and respect for cultural diversity) are covered in the curriculum. Countries where such issues are commonly covered in the curriculum, according to school principals, include the Dominican Republic, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia and Thailand. Countries where such topics are rarely covered include Baku (Azerbaijan), Bulgaria, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan and Moldova.

The coverage of global issues in the curriculum was positively associated with related student dispositions. The strongest associations were between coverage of climate change and global warming in the curriculum and students’ awareness of these issues. Also associated were the coverage of causes of poverty in the curriculum and awareness of migration and movement of people; as well as the coverage of international conflicts in the curriculum and awareness of this topic. However, there was substantial cross-country variation in the relationship between exposure to global and intercultural learning at school and students’ attitudes and dispositions.

Securing equitable opportunities for students to develop global and intercultural skills

The PISA results show important inequalities in access to opportunities to learn global competence. On average across OECD countries, boys were more likely than girls to report participating in activities in which they are expected to express and discuss their views, while girls were more likely than boys to report participating in activities related to intercultural understanding and communication. For instance, boys were more likely to learn about the interconnectedness of countries’ economies, look for news on the Internet or watch the news together during class. They were also more likely to be invited by their teachers to give their personal opinion about international news, to participate in classroom discussions about world events and to analyse global issues together with their classmates. In contrast, girls were more likely than boys to report that they learn how to solve conflicts with their peers in the classroom, learn about different cultures and learn how people from different cultures can have different perspectives on some issues. These gender differences could reflect personal interests and self-efficacy, but they could also reflect how girls and boys are socialised at home and at school.

The findings also show that advantaged students have access to more opportunities to learn global and intercultural skills than disadvantaged students, differences that were largest in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong (China), Korea, Macao (China), New Zealand, Scotland (United Kingdom) and Chinese Taipei. But the data show an interesting pattern: Disadvantaged students are less exposed to global and intercultural learning activities and report less positive attitudes than their advantaged peers. But students attending disadvantaged schools are more likely to be exposed to those learning opportunities. What this means is that the lack of access to learning opportunities does not result from lack of opportunities in disadvantaged schools, but rather from within-school mechanisms that result in lower engagement among disadvantaged students. Thus, when school curricula, educational practices and materials are developed, educators need to keep in mind that not all students are predisposed for global and intercultural learning. Those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds may be facing particular challenges and may require that content or teaching approaches be better adapted to their needs.

Those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds may be facing particular challenges and may require that content or teaching approaches be better adapted to their needs

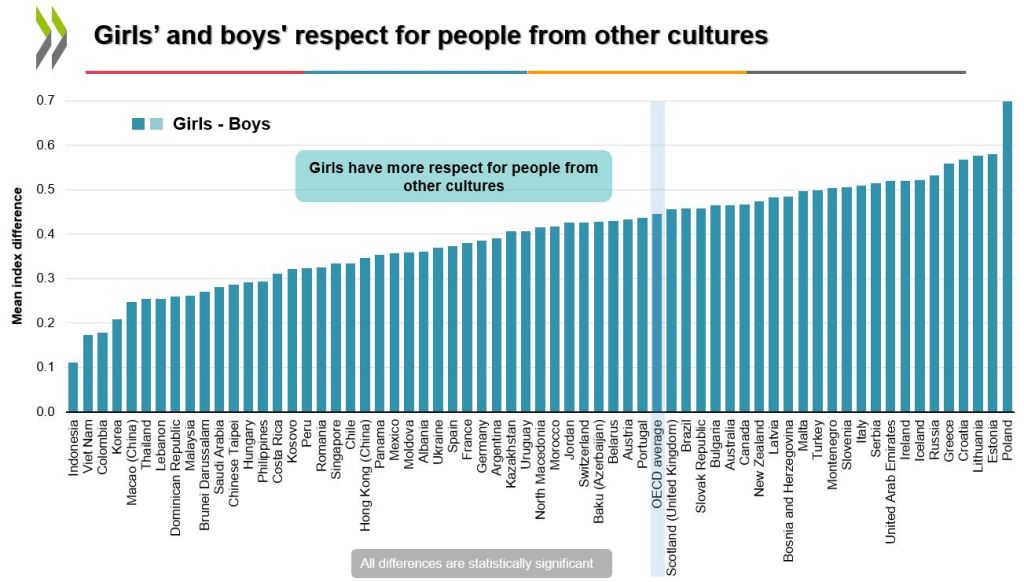

Also when it comes to learning outcomes and student attitudes the findings show clear socio-economic gaps in favour of advantaged students. Furthermore, in most countries, girls were found to have higher awareness of global issues, greater ability to understand different perspectives, greater interest in learning about other cultures, greater respect for people from other cultures, more positive attitudes towards immigrants, greater awareness of intercultural communication, and greater agency regarding global issues. On the other hand, in a majority of countries, boys were more likely to show higher cognitive adaptability than girls.

It is noteworthy that in countries with larger immigrant populations (measured here by more than 5% of students with an immigrant background) the gap in learning outcomes between immigrant and native-born students tended to be less pronounced. In some countries, immigrant students reported higher awareness of global issues than their native-born peers, greater self-efficacy regarding global issues, higher interest in learning about other cultures, greater respect for people from other cultures, higher cognitive adaptability and more positive attitudes towards immigrants. In some countries, having more than 10% immigrant students in school was also associated with more positive attitudes towards immigrants. It seems that more multicultural classrooms could create a culturally rich environment that helps both immigrant and native-born students learn about one another. But this finding holds mainly in long-standing immigrant destinations, suggesting that the positive association may be conditional on successful integration policies.

Promoting an inclusive learning environment

A very high proportion of students in PISA (more than 90%) attended schools where principals reported positive multicultural beliefs among their teachers on all four statements included in the questionnaire. Those questions focused on teachers’ attitudes towards people from other cultural groups. The PISA measure of discrimination at school could be seen as both individual and institutional, as discrimination can be the act of one teacher or a reflection of a more institutional problem.

However, these positive views of principals were not always mirrored in students’ perception of discrimination by teachers in their schools, and those perceptions seem closely related to students attitudes: The PISA results show consistent negative associations between students’ perceptions of discrimination in their school and students’ own perspective taking, respect for people from other cultures, attitudes towards immigrants and awareness of intercultural communication. Interestingly, students’ perceptions of discrimination at school was less strongly correlated with the knowledge aspects of students’ dispositions (i.e. awareness of and self-efficacy regarding global issues) and more with intercultural attitudes towards people from other backgrounds. So students who perceived discrimination by their teachers towards particular groups, such as immigrants and people from other cultural backgrounds, exhibited similar negative attitudes.

If discrimination becomes an institutional problem, then students may develop discriminatory attitudes towards those who are different from them

This highlights the role of teachers and school principals, and perhaps the broader school climate, in countering or perpetuating discrimination by acting as role models. Students are likely to emulate the behaviour of their teachers. If discrimination becomes an institutional problem, then students may develop discriminatory attitudes towards those who are different from them. By contrast, when teachers do not exhibit discriminatory attitudes and set clear rules about intercultural relations, then students may become aware of what constitutes discriminatory behaviour. Teacher support could also act as a protective factor for students who are at risk of being victims of discrimination.

Supporting teachers

Teachers play an important role in promoting and integrating intercultural understating into their practices and classroom lessons. The results don’t generally show a lack of confidence in teachers’ ability to do so or an unwillingness to promote these topics. Most teachers reported that they are confident in their ability to teach in multicultural settings. In fact, more than 80% of students attended a school whose teachers reported a high degree of self-efficacy, as measured by five statements: “I can cope with the challenges of a multicultural classroom”; “I can adapt my teaching to the cultural diversity of students”; “I can take care that students with and without migrant backgrounds work together”; “I can raise awareness for cultural differences amongst the students”; and “I can contribute to reducing ethnic stereotypes between the students”.

At the same time, teachers reported a high need for training in certain areas, such as teaching in multicultural and multilingual settings, teaching intercultural communication, teaching second languages and teaching about equity and diversity. Indeed, the data show highly uneven teacher participation in relevant professional development activities. Across the 18 countries with comparable data, the most common activity was training for teaching about equity and diversity (about 45% of students attended schools where teachers have taken this training activity). By contrast, fewer teachers received professional development on teaching in multicultural or multilingual settings, second-language teaching, or teaching intercultural communication skills, and even fewer participated in such training activities in the previous 12 months.

The parent factor

Fourteen countries also asked parents questions that mirrored those in the student questionnaire. One set of questions focused on awareness of global issues, another on interest in learning about other cultures and a third on parents’ attitudes towards immigrants. The findings show that the parents of students in Croatia, Germany, Ireland and Italy were more aware of global issues than the parents of students in Brazil, Chile, Hong Kong (China), Korea, Macao (China), Mexico and Panama.

Importantly, students’ awareness of global issues was positively associated with levels of awareness of global issues among parents across all participating countries, even after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile.

As for interest in learning about other cultures, parents in Croatia, the Dominican Republic and Germany reported the greatest interest, while parents in Hong Kong (China), Italy and Macao (China) reported the least interest. In all countries except Panama, students’ interest in learning about other cultures was positively associated with their parents’ interest in doing so. Furthermore, a positive association was found between parents’ attitudes towards immigrants and those of their children across all 14 countries that collected data from the parents’ questionnaire.

Parents and teachers can play important and complementary roles in developing a positive intercultural and global outlook among adolescents

These results highlight the importance of parenting and the home environment in promoting global and intercultural interests, awareness and skills. Parents and teachers can play important and complementary roles in developing a positive intercultural and global outlook among adolescents. Parents can transmit knowledge about global issues and also act as role models in defining their children’s behaviour. Parents who show interest in other people’s culture, tolerance towards those who are different from them and awareness of global issues that affect us all are likely to raise children who share those attitudes. This, in turn, can help schools cultivate a climate that embraces those positive attitudes.

Communities can also play an important role

Contact with people from different cultures has the potential to stir curiosity, open minds and create understanding. Students in PISA 2018 were asked whether they have contact with people from other countries in different settings: at school, in their family, in their neighbourhood and in their circle of friends.

On average across OECD countries, 53% of students reported having contact with people from other countries in their school, 54% in their family, 38% in their neighbourhood and 63% in their circle of friends. However, there were substantial variations in those proportions between countries. The proportion of students who reported having contact with people from other countries at school ranged from 70% to 78% in Albania, Germany, Greece, Italy, New Zealand, Panama, Singapore, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei and the United Arab Emirates, but from just 20% to 30% in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey and Viet Nam. Those results were mirrored by findings for other settings where contact with people from other countries takes place, such as the family, the neighbourhood and the circle of friends.

In general, having contact with people from other countries at school (and in the family, neighbourhood and circle of friends) is positively, weakly to moderately, associated with students’ intercultural skills and attitudes towards living with others. The most notable associations were found between having contact with people from other countries at school and students’ self-efficacy regarding global issues, cognitive adaptability, interest in learning about other cultures, respect for people from other cultures, ability to understand different perspectives and understanding of intercultural communication.

In less diverse countries or in education systems that are highly stratified, educators may have to make special efforts to ensure that their students benefit from cultural exposure

The positive associations may suggest that contact between people of different origins and cultures could foster understanding and mitigate prejudice. In multicultural societies, contact arises naturally at school and beyond. However, in less diverse countries or in education systems that are highly stratified, educators may have to make special efforts to ensure that their students benefit from cultural exposure. Examples for that are student exchange or study abroad programmes that offer an immersive experience of another culture. While these programmes tend to be expensive, in the digital age educators can also use online platforms to organise collaborative activities based on the shared interests of their students. Engagement with local communities, such as visiting a community centre, a place of worship or a local market, is another method of introducing students to the diverse cultures existing within reach of their school.

The role of multilingual skills

Speaking multiple languages is a valuable skill that improves employability and fosters a range of abilities that extend beyond the realm of language proficiency. It has the potential to promote social cohesion and intercultural dialogue by opening the door to a range of content, including literature, music, theatre and cinema. By doing so, multilingualism brings down barriers and gives young people direct access to content that would otherwise be inaccessible.

The associations between speaking two or more languages and students’ attitudes were positive in almost all countries. This may reflect that language learning contributes to improving attitudes, but also that students who have positive global and intercultural attitudes tend to engage in learning multiple languages. Speaking two or more languages was positively associated with awareness of global issues, self-efficacy regarding global issues, cognitive adaptability, interest in learning about other cultures, respect for people from other cultures, positive attitudes towards immigrants, awareness of intercultural communication and the ability to understand the perspectives of others.

On average across OECD countries, 50% of students reported that they learn two or more languages at school, 38% reported that they learn one foreign language and only 12% reported that they do not learn any foreign language at school. The largest proportion of students (more than 60%) who reported that they do not learn any foreign language at school were observed in Australia, New Zealand and Scotland (United Kingdom). By contrast, in 48 countries, more than 90% of students reported that they learn at least one foreign language at school.

In conclusion

In our times, global connectedness is no longer just an issue for those who travel to faraway places, but it has arrived at everyone’s doorsteps. At work, at home and in the community, people need to engage with different ways of thinking and different ways of working, and they need to understand different cultures. The foundations for this don’t all come naturally, but need to be built. We are all born with what political scientist Robert Putnam calls “bonding social capital” – a sense of belonging to our family or other people with shared experiences, cultural norms, common purposes or pursuits. But it requires deliberate and continuous efforts to create the kind of “bridging social capital” through which we can share experiences, ideas and innovation, and build a shared understanding among groups with diverse experiences and interests, thus increasing our radius of trust to strangers and institutions.

The findings from the world’s first assessment of global competence highlight that public policy can make a real difference: The schools and education systems that are most successful in fostering global knowledge, skills and attitudes among their students are those that offer a curriculum that values openness to the world, provide a positive and inclusive learning environment, offer opportunities to relate to people from other cultures and have teachers who are prepared for teaching global competence.

Getting this right is important. The global competence of our youths today may shape our future as profoundly as their reading, math and science skills

Getting this right is important. The global competence of our youths today may shape our future as profoundly as their reading, math and science skills. Not least, societies that value bridging social capital and pluralism will be able to draw on the best talent from anywhere, build on multiple perspectives, and be best positioned to nurture creativity and innovation.

Read more: