By Rowena Phair

Project Leader, OECD Directorate for Education and Skills

Key points:

– A critical element in addressing the legacies of colonialism is to ensure that every Indigenous child has a strong start in life.

– A top-down and one-size-fits-all approach to early learning misses the opportunity to tailor and respond to the needs and interests of particular communities.

– Partnerships with Indigenous communities are at the heart of smart approaches to improving Indigenous children’s early development.

The discovery of unmarked graves of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in Canada who were forcibly placed into church-run residential schools is a shocking insight into the realities of assimilation policies. As Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said, it is “a shameful reminder of the systemic racism, discrimination, and injustice that Indigenous peoples have faced”. It also shows that the true costs of colonialism on Indigenous peoples around the world has yet to be fully exposed.

The legacies of colonialism are multi-faceted and, in some cases, embedded across generations. Widespread reconciliation and the re-establishment of Indigenous autonomy will undoubtedly take sustained commitment and action on many economic, environmental and social issues. One especially critical element is how well education systems support Indigenous children and their families to ensure that every Indigenous child has a strong start in life.

Children from low socio-economic or other challenging backgrounds do not always achieve a sufficient rate of early development to enable them to succeed later in school. For these children, receiving additional support during their early years may be their only chance to start and benefit from school on an equitable basis with other children. Nonetheless, parents whose own experiences of education were of not being safe will rightly be cautious about entrusting their young children into the hands of “professionals” within mainstream institutions that were not designed by or with their communities. Keeping your child safe from potential harm is a fundamental pillar of good parenting.

One especially critical element in addressing the legacies of colonialism is how well education systems support Indigenous children and their families to ensure that every Indigenous child has a strong start in life

Governments have tried financial incentives and even financial penalties to encourage parents who are cautious or reluctant to place their children into early childhood education and care settings. These approaches can achieve partial success but miss the opportunity to build partnerships and trust with parents and communities, which would eliminate any ongoing perceived need to default to carrots or sticks.

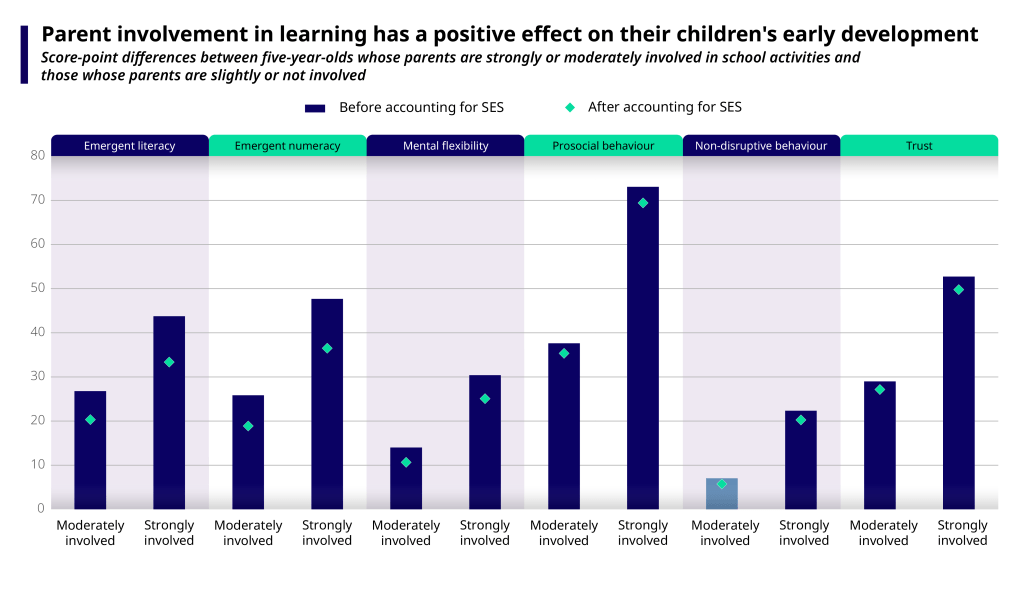

Top-down and one-size-fits-all provision also misses the opportunity to tailor and respond to the needs and interests of particular communities. Indigenous parents often express their strong preference that their culture and languages are incorporated into early learning approaches for their children, as well as the ability for parents and other community members such as elders to have active roles. OECD data on five-year-old children’s development shows clearly that children do better when their parents are actively involved in their learning.

Note: Statistically significant differences are shown in a darker tone. SES = Socio-economic status

Source: OECD International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study database, 2020

The magnitude of these benefits ranges from 3 to 12 months of expected learning progression, according to data from the OECD International Early Learning and Child Well-being study. These benefits accrue similarly for boys and girls and for children from different socio-economic groups. Around one third of parents is regarded by teachers as strongly involved, compared to a similar proportion that is regarded as slightly or not involved.

OECD data clearly shows that parents’ activities with their children, such as reading with them and having back-and-forth-conversations, build children’s language and other cognitive skills, as well as their social-emotional well-being.

Partnerships between educators and parents also help to optimise children’s learning across home and school/centre settings. Again, OECD data clearly shows that parents’ activities with their children, such as reading with them and having back-and-forth-conversations, build children’s language and other cognitive skills, as well as their social-emotional well-being. Early educators can help parents to support their young children’s development, through providing advice and encouragement on how to do so.

An analysis of promising approaches in achieving significant and sustained gains for Indigenous children shows that smart approaches are needed. These approaches put partnership with Indigenous communities at the heart of design and implementation. They incorporate culturally responsive policies and practices, and take a child-centred, holistic approach to early development. They commonly involve early support for families, as well as attention to the capabilities of early educators in working effectively with Indigenous children and their families. The recruitment and training of local Indigenous early educators is often a key strand of successful approaches.

To achieve significant and enduring positive change, education systems need to work on multiple fronts simultaneously.

The issues affecting Indigenous children’s learning outcomes are deep and longstanding. Thus, to achieve significant and enduring positive change, education systems need to work on multiple fronts simultaneously. While this may be challenging for some systems, a comprehensive and sustained strategy, in partnership with Indigenous communities will best enable every Indigenous child to achieve a strong and equitable early start.

Read more:

- Paper | A Strong Start for Every Indigenous Child

- The OECD’s work on improving education outcomes of Indigenous students

- Paper | Improving education outcomes for students who have experienced trauma and/or adversity

- Blog | Is curiosity a key to better early learning?

- Blog | Gender norms are clearly evident at five years of age

- Full international report | OECD International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study

- The OECD’s wider work on child well-being

Photo: Simon Blakesley