By Yanjun Guo

Consultant, OECD Directorate for Education and Skills

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has brought into sharp focus the critical role professions such as nurses and teachers play in keeping society afloat in times of crisis. Despite their importance, tertiary-educated workers with a degree in nursing or education are often poorly paid compared to others, and the share of students graduating from these fields of study is among the lowest.

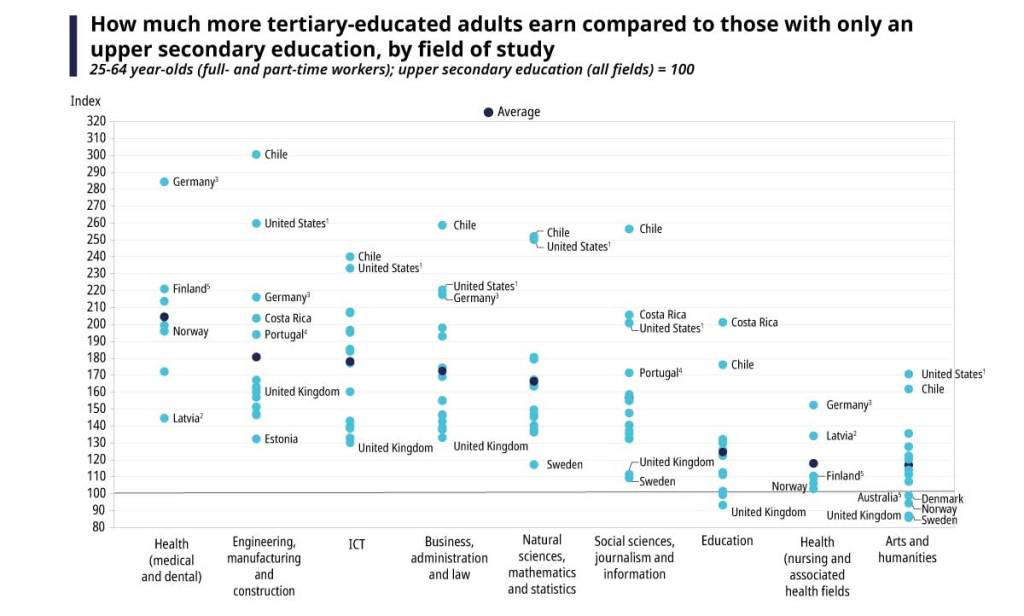

Our latest Education Indicators in Focus brief investigates the earnings difference and the share of tertiary graduates across different fields of study before the COVID pandemic. On average across OECD countries with available data, workers with a tertiary degree in education or nursing and associated health fields earned, at most, 30% more than those with only an upper secondary education. In contrast, those with a tertiary degree in medical and dental health fields, engineering, manufacturing and construction, information and communication technologies (ICT) and business, administration and law earned at least 70% more.

Earnings advantage may reflect, to some extent, the interaction of supply and demand of skills in the labour market. Our analysis finds that broad fields of study associated with an above-average earnings advantage – such as business, administration and law, and engineering, manufacturing and construction – also tend to receive a higher share of tertiary graduates on average across countries with available data. The share ranges from 26% in the United States to 44% in Germany and Switzerland. Meanwhile, students are less likely to graduate from education or the arts and humanities, fields with a below-average earnings advantage.

However, the wage premium cannot always balance supply and demand of skills. For example, in spite of strong earnings incentives, ICT-related fields account for the lowest share of graduates in most countries with available data. Other factors, such as selectivity at entry, personal interests and misinformation on the labour market may influence students’ field choice. Policy interventions such as the public financing of tertiary education or the social benefits provided in some countries may also reduce the pressure on students to select a field based on potential earnings alone, while flexible labour markets may open up a variety of occupations to students beyond their direct field of study.

Policy makers need to consider ways to increase the attractiveness of fields of study such as nursing and teaching, which are essential to society, but less rewarded in the labour market

But more importantly, the COVID-19 health crisis has revealed that market mechanisms alone may not be sufficient to ensure essential services to society are fulfilled and accounted for. Shortages in occupations such as nurses and teachers, already strained before the pandemic hit, have brought to the fore the importance of ensuring a sufficient supply of skills that can sustain societal needs well in to the future. Policy makers will need to consider ways to increase the attractiveness of these fields of study, which are essential to society, but less rewarded in the labour market.

This will be particularly important as the demand for tertiary education has been rising steadily. Since 2000, the share of tertiary-educated adults has increased by more than 10 percentage points, and there is still a growing demand for tertiary education among young people. Understanding students’ choice of field of study becomes critical to ensure students’ acquisition of skills and choice of fields of study aligns with the needs of tomorrow’s economies and societies. But beyond market demand, it will be crucial for policy makers to build on the lessons of the pandemic and encourage the attractiveness of fields of study that provide essential services to society, though they may fall through the cracks of traditional market mechanisms. Some countries have already taken a step in this direction. If more countries follow, we may be able to build the skillset needed for a more resilient society.

Read more:

- Education Indicators in Focus – How does earnings advantage from tertiary education vary by fields of study?

- Education at a Glance 2020

- Why Education at a Glance data is crucial during the COVID-19 crisis

- Lessons for education during the coronavirus crisis

- The OECD coronavirus (COVID-19) policy hub

Photo: Shutterstock/Adam Secgin

Note on figure:

Fields of study are ranked in descending order of average relative earnings for the countries with data available.

1. Data refer to the field of study at bachelor’s level.

2. Earnings net of income tax.

3. Earnings refer to academic programmes only.

4. Arts and humanities does not include the subfield of languages.

5. Year of reference 2016.