By Andreas Schleicher, OECD Director for Education and Skills

The foundation for our shared world

Education has created an amazing world around us. Education shapes our cultures, economies, and democracies. It helps us live with ourselves, with others, and with the planet. And it helps us trust in the power of co-operation, grounded in rules, in shared values, in evidence, even in the middle of a war. Yet past models of education have also left us with troubling disconnects: The disconnect between the infinite growth imperative and the finite resources of our planet; between the financial economy and the real economy; between the wealthy and the poor; between our institutions and the voicelessness of many; between what is technologically possible and the social needs of people.

Reimagining education in times of crisis

If we want to see a different world, we need to build different education systems. But how can we do that? Ukraine’s First Lady Olena Zelenska dedicated the fifth Summit of First Ladies and Gentlemen to that question. To prepare for the Summit, she commissioned the large-scale survey ‘Education as a tool for shaping personal resilience, social capital, and a culture of peace’ which collected data from students, teachers and parents in 14 countries[1]. The survey was developed and implemented by the Centre for Social change and Behavioural economics in collaboration with Deloitte, and with the assistance of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as well as support from the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, the Education Cannot Wait fund and the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE). The results provide profound insights into how students, teachers and parents see today’s schools and how they imagine their future.

Education through the eyes of students

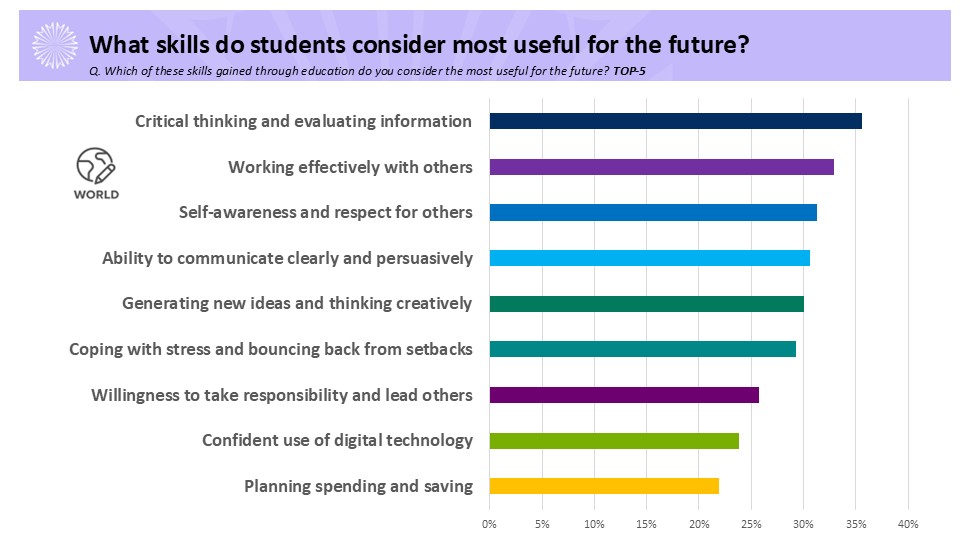

What purposes of education are most important? Strikingly, from among the respondents it was the students who offered the most daring responses. Across the 14 participating countries, students put critical thinking and evaluating information first. In fact, in Ukraine more than half of students chose critical thinking as the most valuable skill for the future. Students are looking for better tools to navigate today’s world of mis and disinformation, where social media help us connect and collaborate, but also trap us in echo chambers that reinforce our own views, shut out different perspectives and deepen social divides. They know they need the skills to question assumptions and look beyond surface claims, to make reasoned and ethical judgments, to weigh evidence, to triangulate viewpoints and compare perspectives, and identify biases or gaps in arguments.

Social skills came as a close second in students’ priorities, and in Finland and Estonia, working effectively with others was students’ first choice. That is interesting because social skills often don’t get much play in schools. We may talk about them in curricula, but then we put students behind individual desks, and give them tests where they have to show they are better than their neighbour.

Next on the list were self-awareness and respect for others, creativity and resilience, all among capabilities that modern societies have elevated from soft to hard skills.

More concerning is that students gave comparatively low priority to taking responsibility and leading others. Perhaps this is a reflection on schools where students are still often passive consumers of knowledge, not active learners, not actively engaged in taking responsibility for themselves and for others. Changing this is important. Today’s students will be tomorrow’s startups; they should not just learn for jobs but learn to create jobs. That requires curiosity, imagination, entrepreneurship, and resilience, the ability to see failure as an opportunity for growth. That, in turn, relies on students owning the purpose of their learning and on being part of the design of their learning environments; on mastery, the desire to get better and better at what we do; on relatedness, our desire to feel valued and supported; and on autonomy, our ability to deploy a range of learning strategies in self-directed ways.

Country Insights

•Ukraine – More than half (54%) emphasize critical thinking as the most valuable skill for the future.

•Finland & Estonia – Stand out for valuing teamwork (40–41%) alongside critical thinking.

•Lithuania & Denmark – Put the highest weight on resilience (Lithuania 42%, Denmark 42%), showing a focus on handling stress and recovery.

•Japan – Prioritizes creative thinking and innovation (44%) much more than the global average.

•South Africa – Much lower share for critical thinking (23%), compared to other countries.

•USA & UAE – Strongly emphasize self-awareness and respect for others (USA 38%, UAE 32%) alongside communication.

•Mexico – Lower compared to others in communication (22.5%), but strong in teamwork (37%).

•Turkey – Nearly half (47%) highlight critical thinking, showing alignment with Northern Europe on this skill.

Bridging schools and futures

The survey also looked at how education aligns with the dreams and aspirations which students have for their future. Worryingly, on average just 26% of students across the 14 countries believe that schools prepare them for independent life. When asked in what ways their school helps them navigate the world of professions, just 43% said they are introduced to different occupations, just 39% said they are helped to understand the skills needed for different careers, and just 37% said they are supported in identifying their own strengths relative to different fields. Of course, these averages hide considerable variation and some countries do better. However, the overall picture is troubling: In most countries, social background plays a bigger role in shaping the aspirations students than talent and motivation. The job expectations of students bear little relation to actual patterns of labour market demand. Most of the jobs which young people want remain out of reach – their career choices are focused on a limited number of high status jobs which they see in the media but cannot find in the real world. And clearly, the majority of young people are not getting enough career development opportunities which connect them with the right people in work and workplaces and help them understand the opportunities open to them.

We need to change that. School should never be the world of children – the world should be their school. The past was divided – with teachers and content divided by subjects and students separated by expectations for careers; with schools designed to keep students inside, and the rest of the world outside. The future needs to be about integrating different experiences, integrating the world of learning with the world of work, making connections between ideas that seem unrelated, and connecting the dots where the next innovation will come from.

Belonging, safety and personal growth

What about the emotional balance of students? A majority of students experienced happy and confident emotions in the month where the data were collected, at least half of the time. But a large and silent minority of young people had a much less positive outlook on life. Almost a quarter of students felt bored and 17% felt anxious.

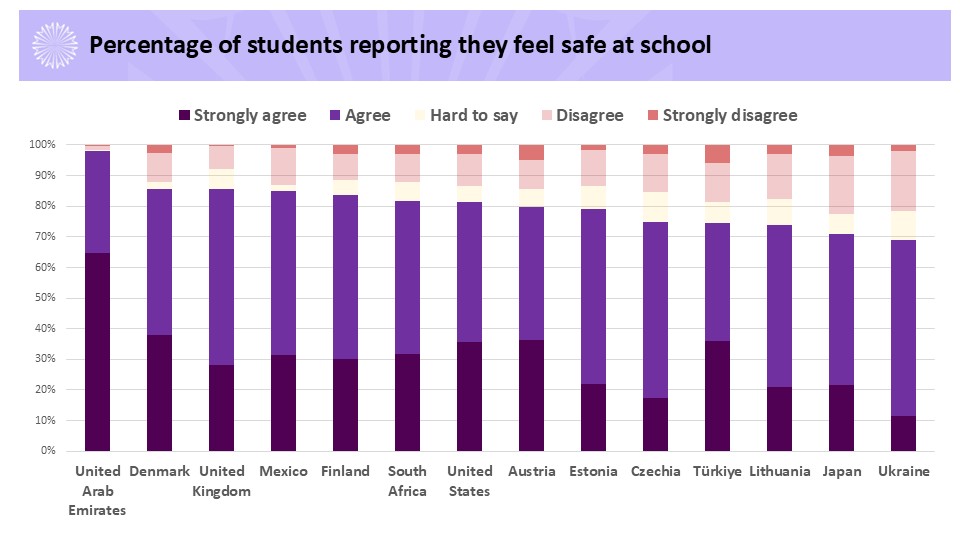

When looking at the basics, in the UAE, virtually all students said that they feel safe in school, and in most countries it was around 80%. In Ukraine it was less than 70%, but if we consider that over 360 Ukrainian schools have been destroyed and ten times that number of schools have been damaged by Russian bombs, that percentage looks actually remarkably high. It tells us that a sense of safety is not just about physical safety, it is very much about emotional safety and the quality of social relationships in school. All of this is tribute to the remarkable work that teachers do in Ukraine every day to give students a sense of safety, normalcy and emotional support in the middle of this war.

When looking beyond the sense of safety towards whether students feel accepted for who they are, the numbers drop, in Japan, Lithuania and Estonia to 70% or below. There are many reasons why we should take those numbers seriously too. First, when students feel accepted, they experience psychological safety, and that safety encourages curiosity and risk-taking in learning; it reduces anxiety and stress, which blocks cognitive function; and it promotes open communication and collaboration. Second, a sense of being accepted boosts engagement. Students who feel seen and valued are more likely to participate actively in class, take ownership of their learning and persist when things get tough. Not least, a sense of belonging is a very basic human need. In schools, it translates into motivation and resilience. Classrooms become richer, more dynamic spaces. Students learn empathy and get better prepared to live and work with other people later in life.

The most concerning aspect is the sizeable minority of students who question whether children have a fair chance to succeed in school if they make an effort. That mindset of equal opportunities and personal growth is so important. Of all the judgements we make about ourselves, the most influential one is how capable we think we are to overcome difficulties. More generally, research shows that the belief that we are responsible for the results of our behaviour influences motivation, such that people are more likely to invest effort if they believe it will lead to the results they are trying to achieve. A growth mindset reframes failure as “not yet,” rather than “not capable.” It encourages grit and a love of learning. Recognising effort also sends a powerful message to students: progress is within your control. And it creates an inclusive classroom culture where all students feel encouraged to strive to become the best version of themselves. In the long term, it builds resilience, and a belief in the potential for personal growth – which is so important for lifelong learning and success.

Importantly, when students were asked about the qualities of teachers who are role models, in most countries treating all students fairly came out on top.

Teachers at the heart of transformation

Like for students, fairness, support, and inspiration also ranked highest when teachers and parents were asked about the most valuable qualities of teachers.

When teachers were asked what is most important in education, preparing students for life was most frequently mentioned, promoting lifelong learning came second and gaining knowledge and skills for future employment came third. This is encouraging but it stands in sharp contrast with how students perceive their school, where they often feel bored, don’t see their dreams aligned with the world of work, and report little support in terms of career guidance.

Are we demanding too much from our teachers. We expect them to have a deep and broad understanding of what they teach and whom they teach, because what teachers know and care about makes such a difference to student learning. And we expect so much more from teachers than what we put into their job descriptions. We expect them to be passionate, compassionate and thoughtful; to encourage students’ engagement and responsibility; to respond to students from different backgrounds with different needs and promote tolerance and social cohesion; to ensure that students feel valued and included and to encourage collaborative learning. And we expect teachers themselves to collaborate and work in teams, and with other schools and parents. Perhaps the biggest challenge of all, we expect teachers to practice today the kind of learning, thinking, and values we hope will shape the world of tomorrow for our children.

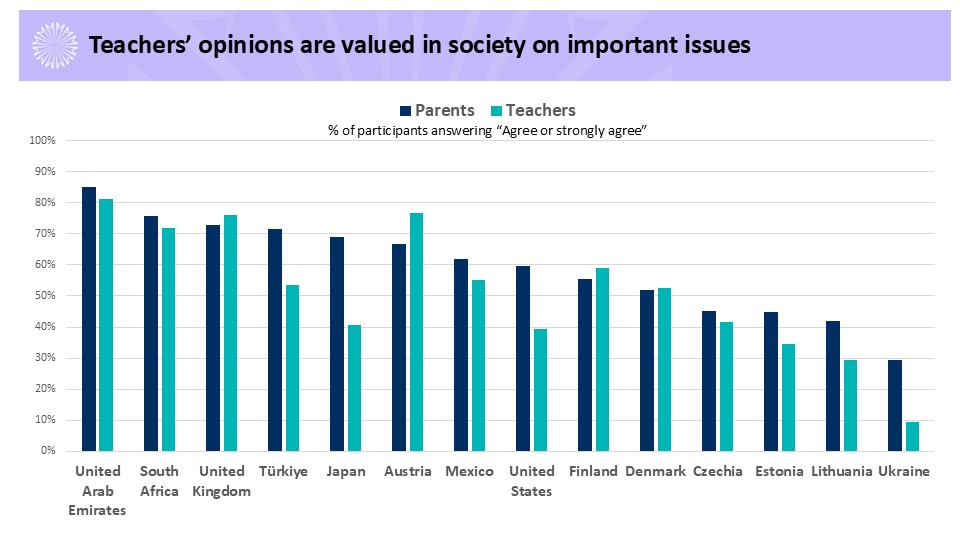

So how are we supporting teachers to meet these expectations? Quality education will always depend on how we value and support teachers. In the UAE, South Africa and the UK, over 70% of both parents and teachers feel that society values teachers’ opinions on important issues. But in Ukraine that share is below 30% among parents and below 10% among teachers.

Are teachers paid fairly for what they do? The UAE is the only country where more than 70% of parents say yes, in Ukraine it is a bare 23%, and when teachers were asked themselves, just 3% of Ukrainian teachers felt they were fairly paid. Still, salaries are rarely the most important factor in the attractiveness of the teaching profession. In Europe, Luxembourg pays its teachers best, but Luxembourg faces huge teacher shortages. In Finland, salaries are comparatively low, and yet 10 applicants are queuing up for every teaching post. What this says is that money only gets us so far. Money is an obvious extrinsic de-motivator, when salaries are inadequate then teachers quit, but money is rarely an intrinsic motivator for people working in education. What makes a job attractive is always a combination of the social status of the job, the contributions people feel they can make in the job, and the extent to which they feel their work is valued and supported. We all know that the quality of education will never exceed the quality of our teachers, but the quality of teachers will never exceed the ways in which societies value and support their teachers.

So what do parents and teachers think about the support of governments for teachers? The views among teachers vary across countries, but apart from the UAE, Austria and the UK, less than two-third of teachers feel that the government really supports the development and well-being of teachers, and in some countries the numbers drop to a few percent.

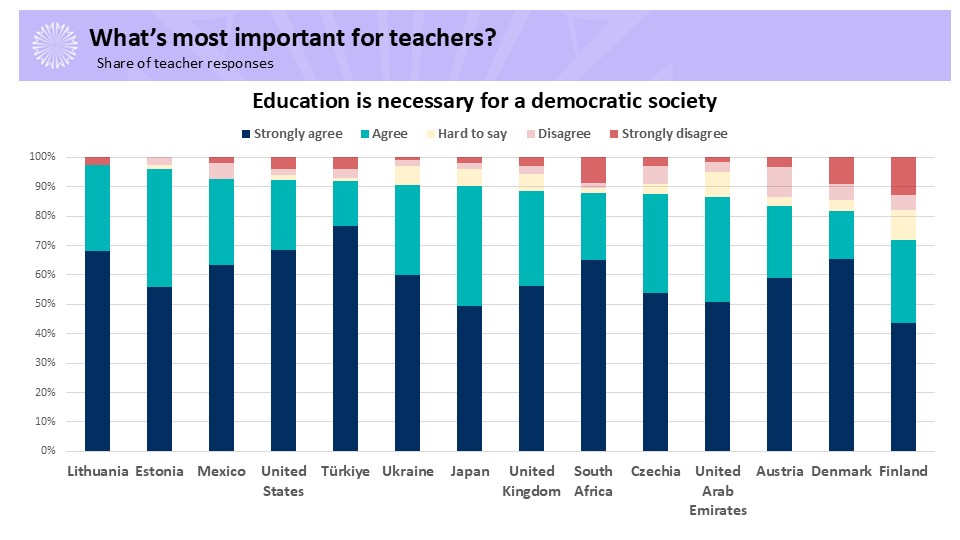

Education for democracy and peace

On a more positive note, in all but one of the 14 countries, over 8 out of 10 teachers see education as a foundation for a democratic society and for peace. When asked what can nurture a culture of peace among students, teachers put developing empathy, tolerance and respect for different opinions first. Teaching about human rights and responsibilities came second, followed by peaceful conflict resolution. This is important because the foundations for this do not come naturally. We are all born with a sense of belonging to our family or to people with shared experiences. But it requires good education to create the capacity to relate to people who are different from us, and to increase our radius of trust to strangers. Education can help students reconcile tensions between competing demands – equity and freedom, autonomy and community, innovation and continuity, or efficiency and democratic process. And education can help students develop a strong sense of right and wrong, a sensitivity to the claims of others, a grasp of the limits on individual and collective action. And education can help students join others, with empathy, in work and in citizenship.

Freedom, democracy and peace are not diplomatic ornaments or beautiful words, they are the heart of education, and they are the pillars on which we build our societies. And if education doesn’t protect them with determination, the world’s tremors will wash away the very foundations of our societies.

AI and the human future

These days it is tempting to see artificial intelligence as a force that steadily erodes human agency. But this should not be a slow retreat – us yielding more and more ground to algorithms. Education can help us become so much more than the sum of isolated, automatable tasks. The rise of AI should sharpen education’s focus on human capabilities that cannot be reduced to code – our consciousness, our capacity to navigate complex relationships and build peace, to exercise ethical judgment in uncertainty, to create something genuinely new.

That is why good education is never a transactional business, but always a social, a relational enterprise. And that is the magic of teaching. That understanding who the students in front of us are, who they want to become and how we can accompany them on their journey. The authentic dialogue, the mentorship, the emotional connection. Education is where social relationships become the common heritage of humanity, and that is how education enables us to design the futures that reflect our values and aspirations.

[1] The study surveyed more than 5,600 respondents – students, teachers and parents in 14 countries, including Ukraine. A separate study was also conducted in Ukraine: 1,067 students took part in this additional survey, and 16 focus groups with parents and teachers were organised.