by Dirk Van Damme

Head of the Innovation and Measuring Progress division, Directorate for Education and Skills

The location of human capital matters: in the 20th century, the United States and several other countries were able to benefit from the pool of skilled people in their populations to progress economically and socially at a much higher rate than their competitors.

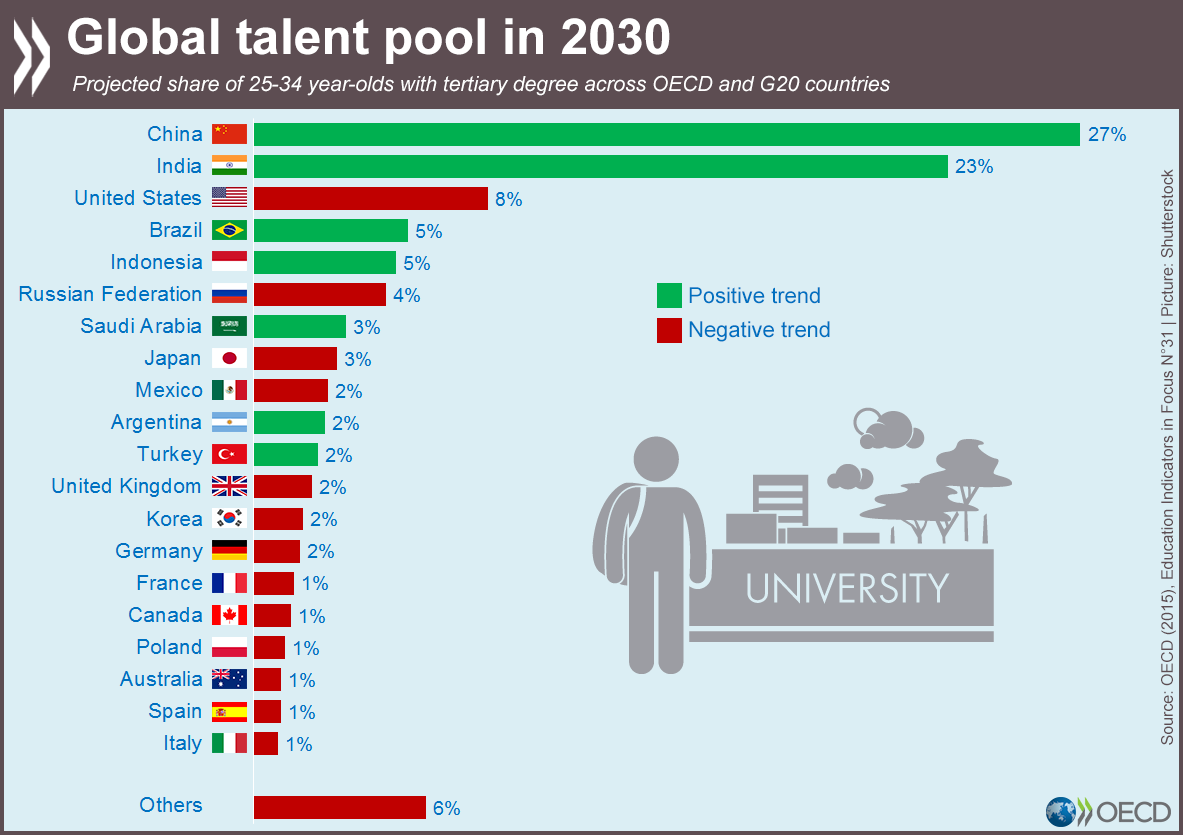

In the first decades of the 21st century, things look much different. The most recent data shown in the latest Education Indicators in Focus brief on the geographical distribution of 25-34 year-old tertiary graduates in OECD and G20 countries show that in 2013 China had already surpassed the United States. Some 17% of all tertiary graduates are found in China, compared to 14% in both the United States and India. The brief also provides a projection to 2030 based on current trends (see the chart above). In 2030, China would be home to 27% of the global pool of highly educated people, and India to another 23%. The United States would follow with only 8%. And of the emerging economies, Brazil and Indonesia would follow with 5% each. Together China and India would be home to half of the world’s highly educated youth.

These data are truly startling; it is difficult to imagine all the possible consequences. One thinks immediately of the impact on the global distribution of skilled labour and the resulting changes in trade, economic growth and global value chains. Policies to preserve the creative research-and-design parts of production cycles in the industrial nations of the 20th century seem rather antiquated. Think, too, of the enormous consequences for the countries that accomplished this modernisation in a much shorter time than the “old” industrialised nations did.

Of course, many will immediately question the quality of these tertiary qualifications. The expansion and mass accessibility of higher education have put pressure on traditional notions of academic excellence in many industrialised countries. The countries that have undergone this transformation even more rapidly will feel the same pressure. But such dramatic changes also transform the notion of academic quality itself. There are no indications that China and India will be more content with second-class academic quality than the United States or European countries are. But a better and more honest answer is: actually, we don’t know. We don’t yet have a reliable yardstick of the quality of learning and the quality of skills among tertiary graduates. It is difficult to imagine a world in which qualifications and skills matter so much without anyone knowing the real value of them. We know from the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) that even in the “old world” the skills equivalence of tertiary qualifications can differ enormously.

Still, the map of the global distribution of the tertiary graduates looks very different from the map of academic excellence, at least as measured by the established global rankings of universities. Despite their flaws, these rankings nurture the notion that academic excellence is still concentrated in the university systems in the United States, the United Kingdom and a few other European countries. Universities in the East are only very gradually making their way into these league tables. The discrepancy between the location of academic excellence and the location of demand for tertiary qualifications may create tensions, which are only partially resolved through international student flows and e-learning. The global demand for high-quality tertiary education cannot be met by many more international students or MOOCs. As emerging countries like China or India make huge investments in creating world-class universities, it will only be a matter of time before they will catch up in quality as much as in numbers.

In the end, these data are good news. The world is rapidly increasing – and levelling – its pool of knowledge and skills. Given the state of the planet and the many challenges facing us, we will need all the brain-power we can develop. Raising human capital will be the only sustainable strategy, not only to enhance individual nations’ productivity and growth, but also to address the many global challenges before us through research, innovation and collaboration.

Links

Education Indicators in Focus, issue No. 31, by Corinne Heckmann and Soumaya Maghnouj

Education Indicators in Focus, issue No. 31, French version

Survey of Adult Skills

On this topic, visit:

Education Indicators in Focus: www.oecd.org/education/indicators

On the OECD’s education indicators, visit:

Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators: www.oecd.org/edu/eag.htm

Related blog post

French version: Talents : un vivier mondial en pleine mutation

Chart source: OECD database, UNESCO and national statistics websites for Argentina, China, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa (http://stats.oecd.org/)