By Pablo Fraser

Analyst, Directorate for Education and Skills

As societies and economies become more complex and demanding, so too do the expectations placed on teachers. Given the crucial role teachers will play in the lives of today’s students (and therefore tomorrow’s workers), governments need to support teachers in meeting these new demands, from integrating new technologies and developing new teaching practices, to managing increasingly diverse classrooms. This is even more true in a world where teaching as a career is losing its appeal and teacher shortages are common. High attrition rates and frequent staff turnover paint a picture of a profession struggling with dissatisfaction, stress and burnout, pushing more and more teachers to quit teaching altogether.

There is therefore an urgent need to better understand the factors that influence the well-being of teachers, as well as their implications on the teaching and learning nexus – research suggests that teacher well-being can impact the effectiveness of teaching, and, consequently, students’ own well-being and learning outcomes.

Based on our accumulated knowledge and evidence on teachers and teaching, the OECD has taken on the task of developing a comprehensive model of teachers’ well-being. The purpose of the teachers’ occupational well-being framework is to serve as a guide for OECD indicators to collect data on these areas and inform policy.

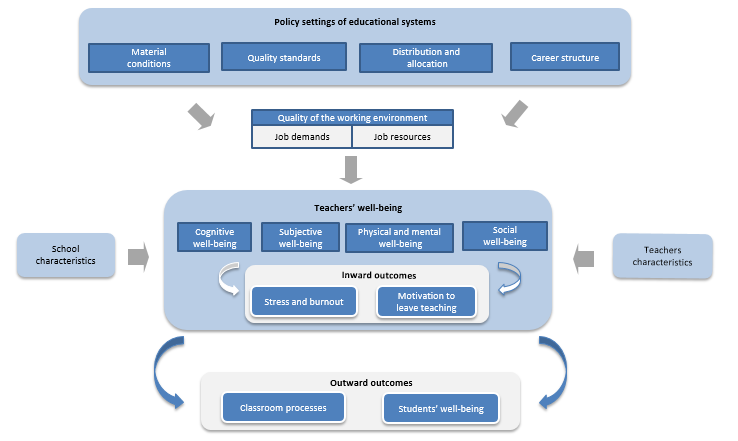

Conceptual framework for teachers’ occupational well-being

The conceptual framework (above) seeks to answer these three crucial questions:

- Which working conditions shape teachers’ occupational well-being? (Upper level of the diagram) – This refers to the factors that affect teachers’ well-being at system level (i.e. the policies that determine how the system runs, for example quality standards) and school level (i.e. a teachers’ working environment). The school-level factors can be divided into two categories: job demands (e.g. workload, performance evaluation etc.) or job resources (e.g. training opportunities, levels of autonomy, etc.).

- What are the core components of teachers’ occupational well-being? (Middle section of the diagram) – The framework defines teachers’ occupational well-being around four key dimensions: cognitive well-being (self-efficacy and concentration at work), subjective well-being (particular feelings or emotional states, satisfaction and purpose), physical and mental well-being (psychosomatic symptoms), social well-being (quality of the working relations).

- What are the expected outcomes of teachers’ occupational well-being? – (Bottom section of the diagram) – The core components of teachers’ occupational well-being mentioned above can have two immediate inward outcomes for teachers: an outcome related to their levels of stress and burn-out, and an outcome related to their engagement with the work and their willingness to stay in the profession. Teachers’ occupational well-being also has outward outcomes in terms of classroom processes (e.g. support for students, frequency of feedback) and direct outcomes on students’ well-being (e.g. students’ motivation and attitude towards learning, students’ self-efficacy).

Given the crucial role teachers will play in the lives of today’s students … governments need to support teachers in meeting these new demands, from integrating new technologies and developing new teaching practices, to managing increasingly diverse classrooms.

The upcoming results of the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (also known as TALIS; to be released in the report TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals) will address a few of the categories of this conceptual framework. For example, motivation to leave teaching will be explored in TALIS 2018 by looking at how many years teachers want to continue working as a teacher. TALIS 2018 will provide an age breakdown of the results in order to see whether younger teachers may be particularly susceptible to express a desire to leave their work.

Also, along with the indicators of levels stress at work across, TALIS 2018 ask teachers as well for their sources of stress

These questions, answered by teachers in 48 countries and economies, are crucial as they allow identifying, based on teachers’ own responses, what aspects of the working conditions of teachers are frequently reported as a source of stress. This identification will help guiding policy in intervening on those issues that might more pressing for teachers’ well-being.

Read more: